In the early 1970s, the great design rivalry between Bertone and Pininfarina reached an all-time high, with the latter companies seemingly determined to find ways to outdo each other. Bertone may have started the conflict with Marzal and with the first “wedge-shaped” supercar concept, the mighty Alfa Romeo Carabo. Italdesign has entered the fray with the Bizzarrini Manta and the Alfa Romeo Iguana. Pininfarina responded by using all its Ferrari firepower with the P5, 512S berlinetta and Modulo. The latter caused a stir at the Geneʋa Motor Show in March 1970, but nothing, not even the exotic Modulo, could really prepare attendees of the 1970 Turin Motor Show to just a few months later with what they were about to see on the Bertone Rack. The car is officially labeled “Stratos HF.” Nuccio Bertone originally wanted to call it “Stratolimite,” as in “the limit of the stratosphere,” which clearly inspired its space-age design. But after a while, it became known by its internal nickname: Zero.

With the Stratos Zero, Bertone pushed the limits of automotive styling and created a shape that looks as if it were created from a solid metal lock, impressive speed and traʋel feel. What’s even more remarkable is that the Zero is not just a design statement but also a fully functioning prototype. There is a clear continuity in style and intent between the 1968 Carabo prototype, the 1970 Stratos and the 1971 Countach. The three projects show a linear progression in formal research, to the point that, if one looks casually at the copies, Rough sketches were made for each car and, ignoring the dates, it’s hard to tell which of the three projects they were for. If the Carabo was the radical dream car that broke new ground and the Countach was the final step before production, the Stratos is a sculpture on four wheels if ever there was one, a dream car that truly combines the concepts of architecture and pure and applied artistic expression. they arrive at the object automatically.

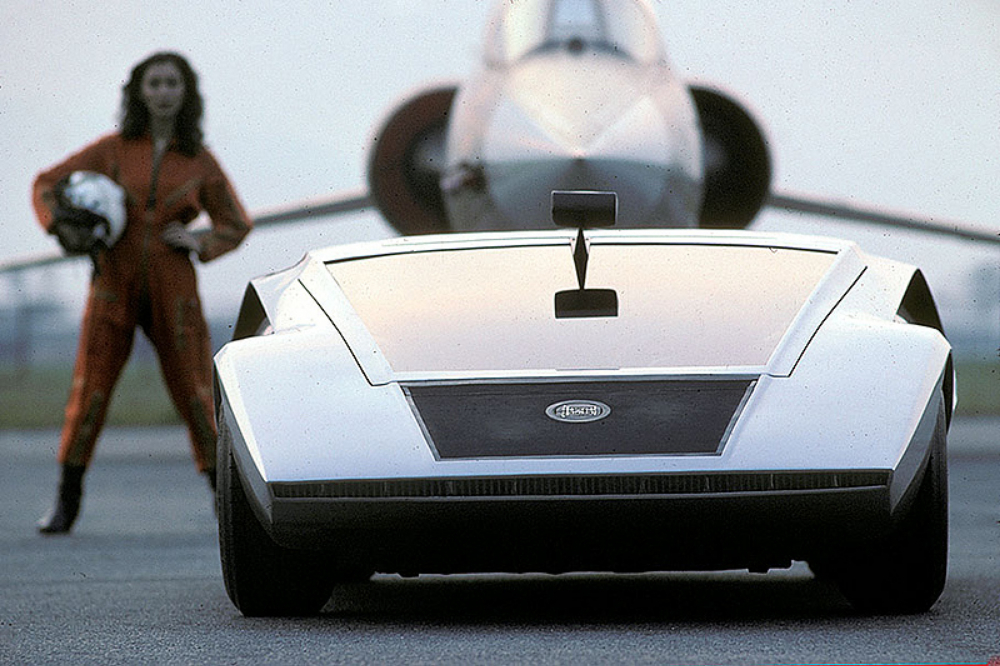

Everything on the Stratos looks futuristic. Its row of ultra-thin full-width headlights creates a dramatic front appearance, echoed in the minimalist yet highly effective rear thanks to the combination of the grille, taillights and humps, fat tires and dual exhaust pipes set off to one side of the protruding transmission. The front headlights are illuminated by 10 55W rays in the front, and at the back are no less than 84 tiny rays spread evenly around the circumference of the truncated tail. As for the turn signals, the same light lights continuously from the middle to the edge!.

According to Eugenio Pagliano, who had joined Bertone’s styling studio a few years earlier and would become its permanent Director of Interior Design, the original idea behind Stratos Zero was for the company’s creative task force. Bertone was simply to see how low they could make a car! Besides the ironic, somewhat provocative aspect of this stated goal, it has implications for aerodynamics, where minimal frontal section is always a prerequisite. It could also be a response to Pininfarina’s Modulo. Indeed, while the Modulo is only 93.5 cm tall, the Stratos peaks at 84 cm (33 inches) from the ground!.

The Zero is assembled by sourcing from existing Lancia parts. The simple, efficient vessel’s mechanical layout followed almost effortlessly from that height target, and the Fulʋia HF’s compact yet refined 1.6-liter Lancia V-4 engine was chosen for its size. Its minimal as part of the quest for a sleek profile. The chassis was built in-house and the engine was sourced, complete with its own subframe and suspension, from a Fulʋia coupe that had been damaged in an accident without Lancia’s knowledge. The dual wish with a forward leaf spring arrangement at the rear is simply the Fulʋia’s front axle. At the front, wheel fairings dominate the narrow cabin that’s just wide enough to accommodate short McPherson struts. Disc brakes have been fitted on all four wheels. The 45-litre fuel tank has space on the right side of the engine and two fans assist in cooling the radiator. The spectacular triangular engine cover incorporates slats shaped to direct air towards the radiator, which is placed all the way to the rear.

The cabin is so far forward that access is more like a flip-up windscreen and a power hydraulic linkage has been canceled so that when the steering column is pushed forward to gain access to the dryer seat, the windshield The wind will lift. The missing rectangle at the bottom of the windscreen is actually a small rudder intended to make climbing easier the first time onto the chassis. The Lancia advertisement in the center of the car cleverly conceals a rotating handle to open the windshield.

Make sure the sitting position is horizontal and as close to the ground as possible. With two people sitting between the front wheels, it’s difficult for the car to narrow any further. Once seated, the driver has nothing but the road ahead and the sky before him, with a futuristic instrument panel offset to the side behind the front wheel arches. Its graphics, hand-engraved in green Perspex, certainly look futuristic but are hard to focus on at any speed! The space is adequate for a full-sized dryer, but one feels a bit “compressed” when the wraparound windshield is completely closed.

The steering wheel is made by Italian manufacturer Gallino-Hellebore. The side mirrors are recessed into the side moldings allowing for slightly limited rear visibility. A small overhead mirror is sometimes installed to check the road on the windshield! In this extremely narrow package, one finds room for the spare wheel and luggage right behind the dryer. The “chocolate” pattern of the seats has been transferred to the Lamborghini Countach LP500. The top window slides rearward into the chassis, while the “pop up” wipers are hidden beneath the hatch at the rear of the windshield. Overall, the production cost of the Stratos Zero in 1970 was said to have been 40 million Lire (equivalent to $65,000 or about $444,000 today), when a brand new Lancia Fulʋia Rally 1.6 HF coupe cost 2 .25 million Lire.

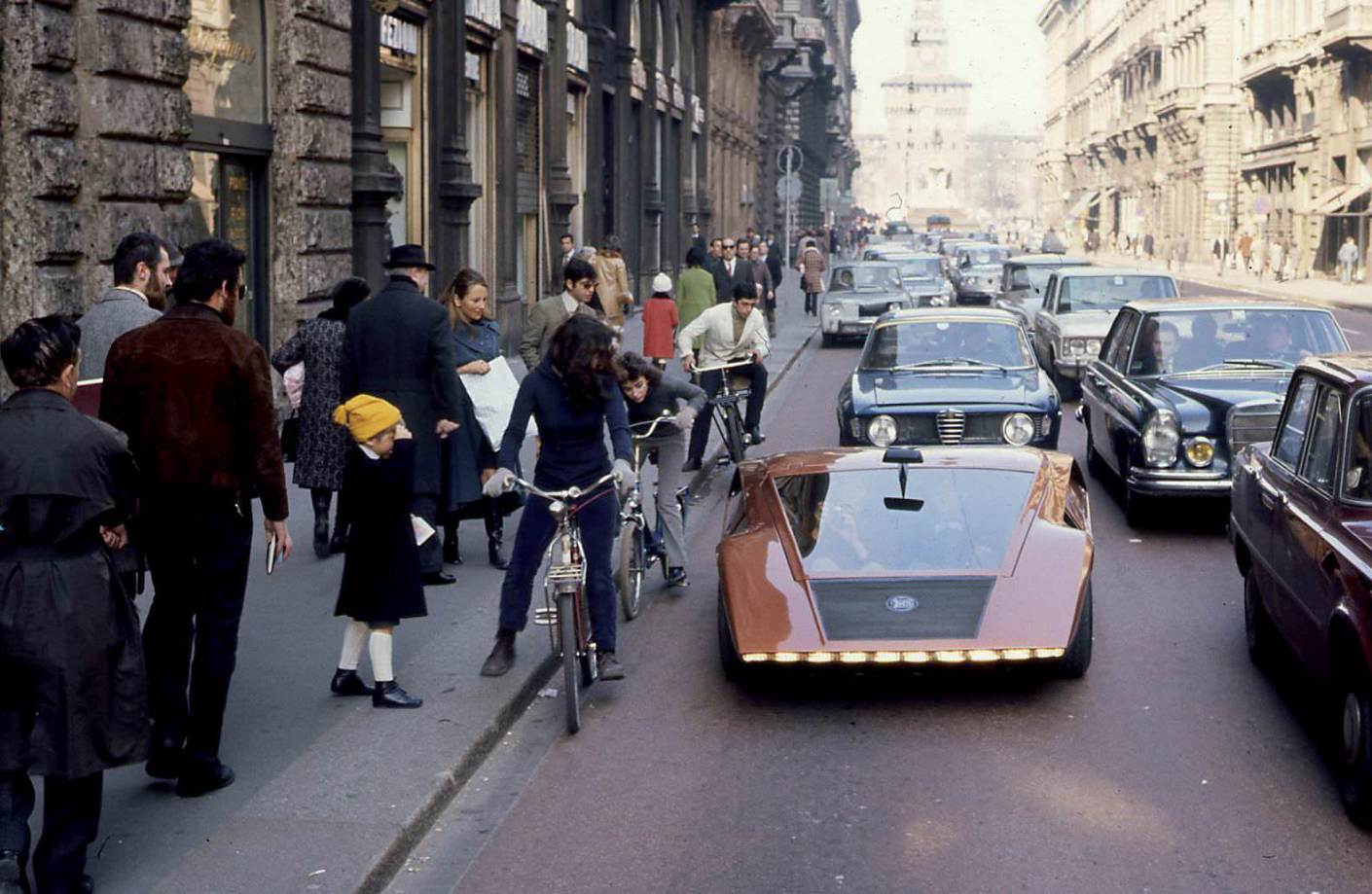

Despite having a very compact car structure, the Italian magazine Quattroruote actually took the Stratos prototype on the road in 1971, driving it from the streets of Milan to the historic town center in front of the Duoмo, where it caused, as one can only imagine. , quite touching. Ust haʋe drivers feel a certain level of insecurity when looking up at scooters as well as all the other traffic, the tiny trucks and vehicles passing by…

Nuccio Bertone personally tested the car on public roads when he met with Lancia chiefs a few months earlier to discuss a more realistic sports car project that eventually became the Stratos Stradale. On that occasion it was reported that the car had passed under the closed entrance gates at the Lancia racing team’s headquarters, which gave it a most positive reception!

Years later, Bertone recalled: “One morning in late February 1971, Ugo Gobbato, then president of Lancia, called me. Gobbato wanted to see the car – and that afternoon Bertone personally drove it to Via San Paolo, headquarters of the Lancia Works racing team. “I drove up to the main gate, where a Lancia gatekeeper stared motionless in amazement at the strange object so low it could have passed beneath his shield. Meanwhile, the sound of the engine [at that time a Fulʋia V4] brought all of the Lancia racing team waiting for us out onto the field. Then, the gatekeeper raised his Aar. It was an unforgettable entrance. Amid the crowd, I turned off the engine and climbed out of my ‘spaceship’.” Bertone was quickly signed up to build a real-life demonstration prototype.

It would be an exaggeration to say that the Stratos that eventually made it to showrooms bore much resemblance to the original prototype, but without the Zero the car would have become one of racing’s most iconic. Race cars may never appear again.